Photos: the Terra Nova in the pack (the image we were reenacting in this post); an LC-130 Herc taking off from Williams Field. Photo: US Antarctic Program Photo Library (http://photolibrary.usap.gov)

I’ve delayed posting any of this for over a year now, even though I started writing it back then. I just didn’t want the way I went out to overshadow the amazing time I had on the ice. But here it is, at long last. The Ross Ice Shelf has claimed a number of people. And maybe just to spite the reenactments, it gave me a nasty sideswipe at the end of our journey.

Our time on the ice was nearly over. McMurdo was shrinking, and every flight out–as many as 3 a day now–seemed like part of the countdown. I took to looking at the passenger manifests posted on the intranet to see who was experiencing the mixed emotions of bag drag the night before flying. Every morning, it seemed, there were more bright blue duffle bags of bedding left outside the doors of the dorm rooms on my corridor, a sign that someone had stripped her/his bed and vanished, up and away. When I thought about having to perform these rituals myself, I almost couldn’t bear it. Not ready to go. But I was spared that kind of performance, as it turned out….

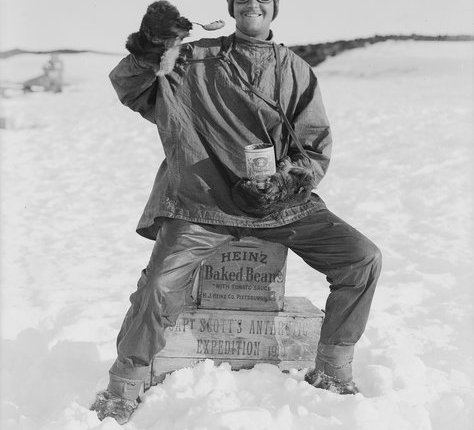

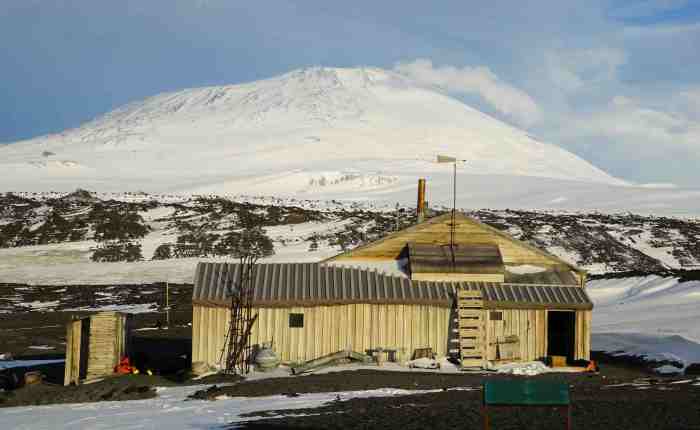

Our last shoot was at Williams Field. In one of the Ponting coffee table books for the centenary, there is a full 2-page spread of a photo of the ship in the sea ice with 2 men standing closer to the camera but still in extreme long shot. We wanted to reenact the photo not with the supply ship, which by then was long gone from the ice pier, but with an air ship. We thought we might shoot this at Pegasus Field when the C-17s started landing, but Pegasus had been in really bad shape, so no wheeled aircraft were able to come and go. This has been a problem in the last few years, and in fact we had attended an SRO lecture about the affects of the slow but inexorable movement of the Ross Ice Shelf and how it was causing Pegasus to come right into the path of volcanic dust blowing in from Black Island as well as some strange bacteria that was contributing to mushing up the runway. So a new runway is in the works. (Update: The new runway, Phoenix, is open, and Pegasus is no more: https://antarcticsun.usap.gov/features/contenthandler.cfm?id=4284)

Anyway, the process of changing over to winter was going more slowly than usual, because people were being ferried out and in exclusively with the smaller slower Hercs. This was causing some anxiety in town, because people would get themselves all ready to go and then face a delay of 1, 2, 3 days. Your stuff is all sitting in cold storage, you’re ready to go physically and mentally, but you don’t. And if you’re a contract worker, you have to keep working while in this limbo. People began to gather by the monitor in 155 just outside the mess hall that provided flight and weather info and to scan passenger manifests. I’m getting ahead of myself here a bit, but I did hear that when I left a couple of days before planned and not in the way I would have wished, I might have displaced a couple of poor souls, and there was some cursing at the 155 monitor. I still feel badly about that.

Back to Willy Field. We wanted to include the Airfield Manager Gary Cardullo in our shot. He’s responsible for keeping the runways in good whack among other things, and what a job he had this year. He was understandably busy, so we kept putting off the shoot, but finally we made a date. We drove out with him–it’s about 7 miles from town–with Katy along to help us and as our liaison. We were carrying a lot of video gear, because we planned to double up on the shot and as we were riding in a van, toting a lot of stuff wasn’t an issue–or so I thought. We sat in the van for awhile chatting. I’ve noticed that many folks who work out in the cold keep the insides of their vehicles really warm, for me uncomfortably so, but then I’m not outside for hours on end every day. Earlier in our stay we’d been fascinated by the spectacle of folks who were driving trucks for the Evolution and waiting in queue for long periods such that they couldn’t keep the engines running indefinitely. To keep warm, some of them would get out of the trucks and use the beds as exercise mats. There’d be someone up on a truck doing push-ups, legs up on the cab.

Gary kept his van quite warm, and when we got out to go wait in the fire station/warming hut where the crew get some respite from the cold, I miscalculated a number of things. It was murky weather outside, cold and blowy and overcast. When the wind hit my face I put my sun goggles on, but they steamed up, and in the murk and because I was hefting a heavy pack over my right shoulder and a tripod in my left arm, I did not see a hill that had formed near the fire station/warming hut steps from the ice repeatedly thawing from heat of said hut, and then re-freezing. So it was nasty ice, hard and slick. I just didn’t see it. Down I went. I was facing the steps with the downhill side of the ice hill to my left, and my legs started to slide that way, which would have made me land uphill a shorter distance, but then I would land on my right side on which I had slung my pack containing my camera and all the pretty Sony lenses. So I swung the pack to go the other way, thinking to right myself, but it was too much weight and I wound up falling on my left side on the downhill side with much more force due to the extra weight and distance, and of course the weight landed on me. Yikes. People helped me up and I thought dang, that was a nasty fall there, but I was OK, maybe. I used the tripod as a cane and hobbled into the hut. Gary brought me a cup of coffee–real coffee–better coffee than I’d had in over a month. I’m OK, I thought, I am just bruised. A couple of days before I had played soccer on the ice and fell diving for the ball several times, but was so well padded and warmed up I didn’t even bruise. I was fine then, so I must be now.

Until I stood back up and pain stabbed me in the hip so cruelly I was nauseated. But I kept saying to myself, and probably others around (I don’t remember a lot of this clearly) I must have sprained my back again or something, I did that years ago and it took a few days but I was OK. But no. We went back out to take the shot, the tripod now absolutely necessary as a crutch, and got in the van to get out as far as we could safely toward the runway, as the Herc’s arrival was in 15 minutes or so and we needed to set the shot up. I think that as we drove out I must have said to Vince that when we were done I needed to go to medical, because by then I thought, the cold air is helping but something is really wrong. I did get out of the van and tried to help, but all I managed to do was grope my way around the van and hop over to Vince’s tripod. There is some GoPro footage that I evidently shot, but I don’t remember doing it. The Herc appeared out of the clouds and glided down and away, and Vince got the shot. He, Katy, and Gary walked over to get another angle on the plane after it had taxied in and passengers were climbing out and then into Ivan the Terrabus, but I couldn’t even make it over there.

Dear reader, here the story grows tedious. Medical. X-Ray. Probable fracture, but it would have to be sorted in Christchurch. Wanting to kick myself, but that would have really hurt. I thought everyone was exaggerating. Medical at McMurdo looks like the 1960s. But I was treated well, at one point stabbed with some sort of pain killer in the thigh and told I had to go home. Tomorrow. And not walk. Honestly at this point I still thought this was all wrong, that I would wake up limping but essentially okay and get on with my planned activities for our last 2 days: cleaning out our lab, labeling and sorting files, making some rounds to say goodbyes and thank everyone, returning my library books, cleaning my room to the specs on the list we were given, taking a few last long walks along the sound to look at the mountains, sharing a last bottle of wine at the Coffee House.

But instead, there was a lot of rigmarole getting back to the dorm and packing, right away. To do this, I was hauled up on a chair by firemen, and was surprised to find people I knew by other jobs doing double duty on fire shift–many jobs entail this, because fire in such a dry place is a thing most dreaded. I was loaned the only pair of crutches they could find at this point in the season, which bizarrely seemed to be made for a child or someone 4 feet tall, but they were better than the tripod. And I was helped by Katy and Vince. Katy packed my personal belongings while I was propped up on my bunk feeling idiotic, and she even went so far as to sleep in my room while my newly-arrived roommate went down the hall into one of the empty rooms for the night. Vince got the work equipment sorted and packed.

The next day I was again carried, this time down the steps, collected by an ambulance, and taken to Willy Field (cursed place!) having been designated a medical evacuation. It took 3 tries to get on a plane. Herc #1 showed up with a cracked window. By the time i had started the too-short-crutch hobble up the cargo ramp it was scrubbed so back into the ambulance I lurched; meantime all the passengers for Herc #2 had arrived, the cargo was all stowed, and there was no room in it for the gurney I had to travel on. So after hours and hours on the runway, I finally got on Herc 3, the last flight out that day. I was joined by another medical evacuee who turned out to have a more serious problem, in the end. About 2 hours into the flight I couldn’t get comfortable at all, so I took one of the Rush Limbaugh pills I had been given. How that guy ever functioned on those, I have no idea. The rest of the flight was like an hallucination.

When I came to they were opening the hatch on the plane and I was struck by the strongest smell of earth, of green growing things, that I have ever experienced. It was intoxicating (on top of the drugs). A month on the ice with no plant life at all, and then wham, what an intense difference. I’ll never forget that rush of smell. It’s there all the time, of course, but we don’t smell it until it goes away for awhile. Off we went into the delicious green humid air in an ambulance to Christchurch Hospital, for a lot of stuff I just cannot remember or seems like it must have been part hallucination. For instance, I woke up to see a very tall Maori man standing next to my gurney in the ER. He said in a very deep voice, “You are lucky. You are first for theatre.” In my fog I thought huh, I’m going to the theatre; will there be Maori dancing? Cool!” But then I asked the Maori man, who introduced himself as an orderly, why we were going to the theatre and he seemed upset. “Didn’t anyone tell you?” Then things snapped into focus–New Zealand, dope, theatre is surgery–and I sat up fast (ouch!) and asked, “Tell me what? What is wrong?” This is how it was confirmed that my hip was broken and required immediate surgery..